On March 11th, 2025, William Ford, the artist who illustrated Two Big Differences, died. He is survived by his wife, the poet Susan Harvey, and his daughter, Belle.

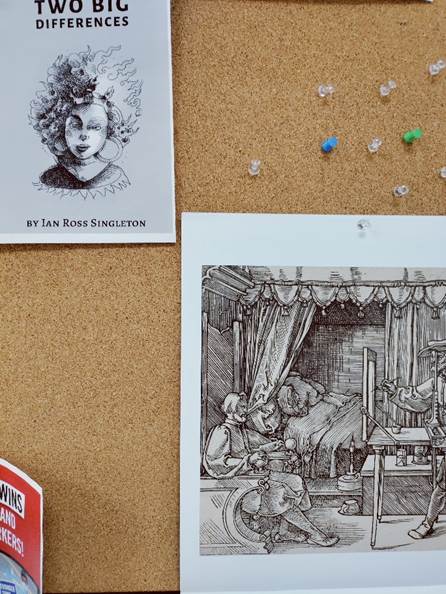

The day I found out, I was of course distraught at the loss of my friend. Sitting in my office, I started looking at some artwork, a calendar of Albrecht Dürer etchings which I’d hung recently. I started looking at Dürer’s use of hatching to make shades. Any visual artist would tell me it’s a common technique. Bill was such an artist, and we had some fantastic conversations, sometimes quite heated!

I had hung the cover of my novel, with Bill’s illustration on it, at a random time and in a random place juxtaposed to the calendar. I did not plan this visual tendency. But there it was.

The crosshatching Bill used crossed slightly over the orientation of the calendar’s lines. I thought it was a hello from Bill, who once thought of becoming a priest.

As far as I know, Bill was born in 1948 outside Chicago, where he grew up.

He told me he wanted to join the priesthood as an act of becoming part of the countercultural movements of the 1960s. But he couldn’t take the vow of obedience.

Irish-American, Bill did not drink alcohol. This refusal came up later when he had moved to New York City. He was an anti-war organizer and decided to enlist in order to urge soldiers to resist the war from within. He was promptly sent to the South, where he was put in a barracks with men who, as he said, would have been in prison if they hadn’t joined the military. When he told them he didn’t drink, they didn’t believe him, held him down, and poured liquor down his throat.

After this violence, they grew to respect Bill (in a way). This respect was helpful when one night people from the community where the barracks was located came to do worse violence to Bill. His new comrades surrounded him and threatened anybody who came near him. The next day, Bill was dishonorably discharged and returned to New York.

An uncle who worked in advertising arranged an interview for him. He took it. When asked a question, his answer was, “I got people to go out in the street and risk their lives. You think I can sell fucking potato chips.”

He never advertised for alcohol or tobacco.

He ended up working with computers, ended up in San Francisco, where I met him.

In January, I finally got to send him an email announcing that I had (also, finally) framed and hung two of the portraits from his illustrations, Valya and Zina.

His reply was terse: “Love it. Happy memories.”

It was not like Bill. But Bill was sick then, and I didn’t know.

Now Bill’s gone. And there will be fewer fantastic, heated conversations.